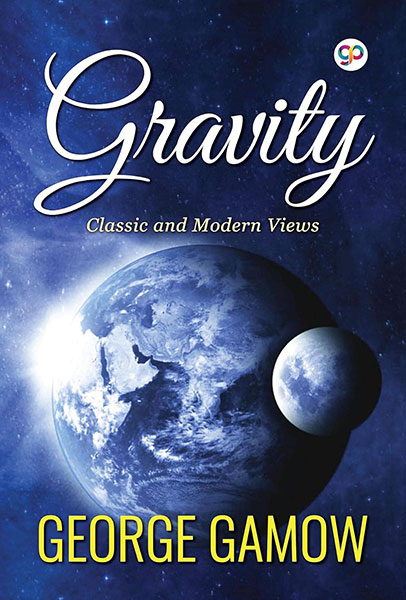

Gravity

Gravity is one of the four fundamental interactions that exist in nature. Understanding gravity is not only essential for understanding the motion of objects on Earth, but also the motion of all celestial objects, and even the expansion of the Universe itself. In this book George Gamow takes an enlightening look at three scientists whose work unlocked many of the mysteries behind the laws of physics: Galileo, the first to examine closely the process of free and restricted fall; Newton, originator of a universal force; and Einstein, who proposed that gravity is no more than the curvature of the four-dimensional space-time continuum. The author has illustrated the book himself with some technical fanciful drawings.

BEST DEALS

About the Author

George Gamow (1904—1968), was a Russian-born American nuclear physicist and cosmologist who was one of the foremost advocates of the big-bang theory, according to which the universe was formed in a colossal explosion that took place billions of years ago. Gamow attended Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) University, where he studied briefly with A.A. Friedmann, a mathematician and cosmologist who suggested that the universe should be expanding. At that time Gamow did not pursue Friedmann’s suggestion, preferring instead to delve into quantum theory. After graduating in 1928, he traveled to Göttingen, where he developed his quantum theory of radioactivity, the first successful explanation of the behaviour of radioactive elements. In 1934, after emigrating from the Soviet Union, Gamow was appointed professor of physics at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. There he collaborated with Edward Teller in developing a theory of beta decay (1936), a nuclear decay process in which an electron is emitted. In 1954 Gamow’s scientific interests grew to encompass biochemistry. He proposed the concept of a genetic code and maintained that the code was determined by the order of recurring triplets of nucleotides, the basic components of DNA. His proposal was vindicated during the rapid development of genetic theory that followed. Gamow held the position of professor of physics at the University of Colorado, Boulder, from 1956 until his death. He is perhaps best known for his popular writings, designed to introduce to the non-specialist such difficult subjects as relativity and cosmology. His first such work, Mr. Tompkins in Wonderland (1939), gave rise to the multivolume Mr. Tompkins series (1939–67). Among his other writings are One, Two, Three...Infinity (1947), The Creation of the Universe (1952), A Planet Called Earth (1963), and A Star Called the Sun (1964).

Read Sample

1. How Things Fall

The notion of “up” and “down” dates back to time immemorial, and the statement that “everything that goes up must come down” could have been coined by a Neanderthal man. In olden times, when it was believed that the world was flat, “up” was the direction to Heaven, the abode of the gods, while “down” was the direction to the Underworld. Everything which was not divine had a natural tendency to fall down, and a fallen angel from Heaven above would inevitably finish in Hell below. And, although great astronomers of ancient Greece, like Eratosthenes and Aristarchus, presented the most persuasive arguments that the Earth was round, the notion of absolute up-and-down directions in space persisted through the Middle Ages and was used to ridicule the idea that the Earth could be spherical. Indeed, it was argued that if the Earth were round, then the antipodes, the people living on the opposite side of the globe, would fall off the Earth into empty space below, and, far worse, all ocean water would pour off the Earth in the same direction.

When the sphericity of the Earth was finally established in the eyes of everyone by Magellan’s round-the-world trip, the notion of up-and-down as an absolute direction in space had to be modified. The terrestrial globe was considered to be resting at the center of the Universe while all the celestial bodies, being attached to crystal spheres, circled around it. This concept of the Universe, or cosmology, stemmed from the Greek astronomer Ptolemy and the philosopher Aristotle. The natural motion of all material objects was toward the center of the Earth, and only Fire, which had something divine in it, defied the rule, shooting upward from burning logs. For centuries Aristotelian philosophy and scholasticism dominated human thought. Scientific questions were answered by dialectic arguments (i.e., by just talking), and no attempt was made to check, by direct experiment, the correctness of the statements made. For example, it was believed that heavy bodies fall faster than light ones, but we have no record from those days of an attempt to study the motion of falling bodies. The philosophers’ excuse was that free fall was too fast to be followed by the human eye.

The first truly scientific approach to the question of how things fall was made by the famous Italian scientist Galileo Galilei (1564—1642) at the time when science and art began to stir from their dark sleep of the Middle Ages. According to the story, which is colorful but probably not true, it all started one day when young Galileo was attending a Mass in the Cathedral of Pisa, and absent-mindedly watched a candelabrum swinging to and fro after an attendant had pulled it to the side to light the candles (Fig. 1). Galileo noticed that although the successive swings became smaller and smaller as the candelabrum came to rest, the time of each swing (oscillation period) remained the same. Returning home, he decided to check this casual observation by using a stone suspended on a string and measuring the swing period by counting his pulse. Yes, he was right; the period remained almost the same while the swings became shorter and shorter. Being of an inquisitive turn of mind, Galileo started a series of

Fig. 1. A candelabrum (a) and a stone on a rope (b) swing with the same period if the suspensions are equally long.

experiments, using stones of different weights and strings of different lengths. These studies led him to an astonishing discovery. Although the swing period depended on the string’s length (being longer for longer strings), it was quite independent of the weight of the suspended stone. This observation was definitely contradictory to the accepted dogma that heavy bodies fall faster than light ones. Indeed, the motion of a pendulum is nothing but the free fall of a weight deflected from a vertical direction by a restriction imposed by a string, which makes the weight move along an arc of a circle with the center in the suspension point (Fig. 1).

If light and heavy objects suspended on strings of equal length and deflected by the same angle take equal time to come down, then they should also take equal time to come down if dropped simultaneously from the same height. To prove this fact to the adherents of the Aristotelian school, Galileo climbed the Leaning Tower of Pisa or some other tower (or perhaps deputized a pupil to do it) and dropped two weights, a light and a heavy one, which hit the ground at the same time, to the great astonishment of his opponents (Fig. 2).

There seems to be no official record concerning this demonstration, but the fact is that Galileo was the man who discovered that the velocity of free fall does not depend on the mass of the falling body. This statement was later proved by numerous, much more exact experiments, and, 272 years after Galileo’s death, was used by Albert Einstein as the foundation of his relativistic theory of gravity, to be discussed later in this book.

It is easy to repeat Galileo’s experiment without visiting Pisa. Just take a coin and a small piece of paper and drop them simultaneously from the same height to the floor. The coin will go down fast, while the piece of paper will linger in the air for a much longer period of time. But if you crumple the piece of paper and roll it into a little ball, it will fall almost as fast as the coin. If you had a long glass cylinder evacuated of air, you would see that a coin, an uncrumpled piece of paper,

Fig, 2. Galileo’s experiment in Pisa.

and a feather would fall inside the cylinder at exactly the same speed.

The next step taken by Galileo in the study of falling bodies was to find a mathematical relation between the time taken by the fall and the distance covered. Since the free fall is indeed too fast to be observed in detail by the human eye, and since Galileo did not possess such modern devices as fast movie cameras, he decided to “dilute” the force of gravity by letting balls made of different materials roll down an inclined plane instead of falling straight down. He argued correctly that, since the inclined plane provides a partial support to heavy objects placed on it, the ensuing motion should be similar to free fall except that the time scale would be lengthened by a factor depending on the slope. To measure time he used a water clock, a device with a spigot that could be turned on and off. He could measure intervals of time by weighing the amounts of water that poured out the spigot in different intervals. Galileo marked the successive position of the objects rolling down an Inclined plane at equal intervals of time.

You will not find it difficult to repeat Galileo’s experiment and check on the results he obtained.[1] Take a smooth board 6 feet long and lift one end of it 2 inches from the floor, placing under it a couple of books (Fig. 3a). The slope of the board will be and this will also be the factor by which the gravity force acting on the object will be reduced. Now take a metal cylinder (which is less likely to roll off the board than a ball) and let it go, without pushing, from the top end of the board. Listen to a ticking clock or a metronome (such as music students use) and mark the position of the rolling cylinder at the end of the first, second, third, and fourth seconds. (The experiment should be repeated several times to get these positions exact.) Under these conditions, consecutive distances from the top end will be 0.53, 2.14, 4.82, 8.5, and 13.0 inches. We notice, as Galileo did, that distances at the end of the second, third, and fourth seconds are respectively 4, 9, 16, and 25 times the distance at the end of the first second. This experiment proves that the velocity

Fig. 3. (a) A rolling cylinder on an inclined plane; (b) Galileo’s method of integration.

of free fall increases in such a way that the distances covered by a moving object increase as the squares of the time of travel. Repeat the experiment with a wooden cylinder, and a still lighter cylinder made of balsa wood, and you will find that the speed of travel and the distances covered at the end of consecutive time intervals remain the same.

The problem that then faced Galileo was to find the law of change of velocity with time, which would lead to the distance-time dependence stated above. In his book Dialogue Concerning Two New Sciences Galileo wrote that the distances covered would increase as the squares of time if the velocity of motion was proportional to the first power of time. In Fig. 3b we give a somewhat modernized form of Galileo’s argument. Consider a diagram in which the velocity of motion v is plotted against time t. If v is directly proportional to t we will obtain a straight line running from (o;o) to (t;v). Let us now divide the time interval from o to t into a large number of very short time intervals and draw vertical lines as shown in the figure, thus forming a large number of thin tall rectangles. We now can replace the smooth slope corresponding to the continuous motion of the object with a kind of staircase representing a jerky motion in which the velocity abruptly changes by small increments and remains constant for a short time until the next jerk takes place. If we make the time intervals shorter and shorter and their number larger and larger, the difference between the smooth slope and the staircase will become less and less noticeable and will disappear when the number of divisions becomes infinitely large.

During each short time interval the motion is assumed to proceed with a constant velocity corresponding to that time, and the distance covered is equal to this velocity multiplied by the time interval. But since the velocity is equal to the height of the thin rectangle, and the time interval to its base, this product is equal to the area of the rectangle.

Repeating the same argument for each thin rectangle, we come to the conclusion that the total distance covered during the time interval (o,t) is equal to the area of the staircase or, in the limit, to the area of the triangle ABC. But this area is one-half of the rectangle ABCD which, in its turn, is equal to the product of its base t by its height v. Thus, we can write for the distance covered during the time t:

![]()

where v is the velocity at the time t. But, according to our assumption, v is proportional to t so that:

![]()

where a is a constant known as acceleration or the rate of change of velocity. Combining the two formulas, we obtain:

![]()

which proves that distance covered increases as the square of time.

The method of dividing a given geometrical figure into a large number of small parts and considering what happens when the number of these parts becomes infinitely large and their size infinitely small, was used in the third century B.C. by the Greek mathematician Archimedes in his derivation of the volume of a cone and other geometrical bodies. But Galileo was the first to apply the method to mechanical phenomena, thus laying the foundation for the discipline which later, in the hands of Newton, grew into one of the most important branches of the mathematical sciences.

Another important contribution of Galileo to the young science of mechanics was the discovery of the principle of superposition of motion. If we should throw a stone in a horizontal direction, and if there were no gravity, the stone would move along a straight line as a ball does on a billiard table. If, on the other hand, we just dropped the stone, it would fall vertically with the increasing velocity we have described. Actually, we have the superposition of two motions: the stone moves horizontally with constant velocity and at the same time falls in an accelerated way. The situation is represented

Fig. 4. A combination of horizontal motion with constant velocity, and vertical, uniformly accelerated motion.

graphically in Fig. 4 where the numbered horizontal and vertical arrows represent distances covered in the two kinds of motion. The resulting positions of the stone can also be given by the single (white-headed) arrows, which become longer and longer and turn around the point of origin.

Arrows like these that show the consecutive positions of a moving object in respect to the point of origin are called displacement vectors and are characterized by their length and their direction in space. If the object undergoes several successive displacements, each being described by the corresponding displacement vector, the final position can be described by a single displacement vector called the sum of the original displacement vectors. You just draw each succeeding arrow beginning from the end of the previous one (Fig. 4), and connect the end of the last arrow with the beginning of the first by a straight line. In plain words for a trivial example, a plane which flew from New York City to Chicago, from Chicago to Denver, and from Denver to Dallas, could have gone from New York City to Dallas by flying a straight course between the two cities. An alternative way of adding two vectors is to draw both arrows from the same point, complete the parallelogram and draw its diagonal as shown in Fig. 5a and b. Comparing the two drawings, one is easily persuaded that they both lead to the same result.

The notion of displacement vectors and their additions can be extended to other mechanical quantities which have a certain direction in space. Imagine an aircraft carrier making so many knots on a north-north-west course, and a sailor running across its deck from starboard to port at the speed of so many feet per minute. Both motions can be represented by arrows pointing in the direction of motion and having lengths proportional to the corresponding velocities (which must of course be expressed in the same units). What is the velocity of the sailor in respect to water? All we have to do is to add the two velocity vectors according to the rules, i.e., by constructing the diagonal of a parallelogram defined by the two original vectors.

Forces, too, can be represented by vectors showing

Fig. 5. (a) and (b) Two ways to add vectors; (c) Forces acting on a cylinder placed on an inclined plane.

the direction of the acting force and the amount of effort applied, and can be added according to the same rule. Let us consider, for example, the vector of the gravity force acting on an object placed on an inclined plane (Fig. 5c). This vector is directed vertically down, of course, but reversing the method of adding vectors, we can represent it as the sum of two (or more) vectors pointing in given directions. In our example we want one component to point in the direction of the inclined plane and another perpendicular to it as shown in the figure. We notice that the rectangular triangles ABC (geometry of the inclined plane), and abc (formed by vectors F, Fv, and Ft) are similar, having equal angles at A and a respectively. It follows from Euclidian geometry that

![]()

and this equation justifies the statement we made concerning Galileo’s experiment with the inclined plane.

Using the data obtained by experiments with inclined planes, one can find that the acceleration of free fall is ![]() (you probably are familiar with the equivalent expression “32.2 feet per second per second”) or in the metric system,

(you probably are familiar with the equivalent expression “32.2 feet per second per second”) or in the metric system, ![]() . This value varies slightly with the latitude on the Earth’s surface, and the altitude above sea level.

. This value varies slightly with the latitude on the Earth’s surface, and the altitude above sea level.

[1]. Not being an experimentalist, the author is not able to say, on the basis of his own experience, how easy it is to do Galileo’s experiment. He has heard from various sources, however, that this is, in fact, not so easy and would recommend that the readers of this book try their skill at it.